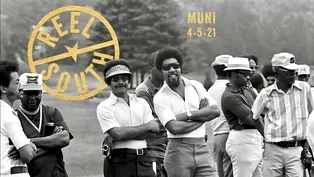

Muni

Season 6 Episode 1 | 26m 5sVideo has Closed Captions

The struggle and joys of Black golfers who integrated a municipal course in Asheville, NC.

A jovial love letter to the game of golf, told by the Black golfers who, despite segregation and racist systems, built a vibrant culture and lasting community on a municipal golf course in Asheville, North Carolina. Narrated by popular singer and golfer Darius Rucker. Directed by Paul Bonesteel

Support for Reel South is made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Center for Asian American Media and by SouthArts.

Muni

Season 6 Episode 1 | 26m 5sVideo has Closed Captions

A jovial love letter to the game of golf, told by the Black golfers who, despite segregation and racist systems, built a vibrant culture and lasting community on a municipal golf course in Asheville, North Carolina. Narrated by popular singer and golfer Darius Rucker. Directed by Paul Bonesteel

How to Watch REEL SOUTH

REEL SOUTH is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipCORTEZ BAXTER: Everybody knows the Muni in western North Carolina, that this is where they learned to play.

If you got thin skin, if you can't take it, wrong place.

[music playing] CY YOUNG, JR.: Muni, that was the Blacks first started playing.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: One of the best places where you see camaraderie with the white and the Black.

PETE MCDANIEL: It's you, the golf ball, and the golf course.

No one can influence that-- no one.

[theme music] [birds chirping] [funky music playing] ♪ ♪ CORTEZ BAXTER: I got into golf and really started getting just swamped with failure and mistakes and frustration.

I said, this is my game!

[laughs] This is my game.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Exercise, get what they buddies, have fun, you know.

Even the preachers get out there.

And they cuss every now and then.

PETE MCDANIEL: Obsession is the word, and it's pure insanity.

CY YOUNG, JR.: It's something different every time you swing the club.

DAL RAIFORD: I believe we all play the game for the same thing, and we have for 400 years.

That emotional feeling of impact.

That's the moment that we play for.

DWIGHT BRYSON: And I play every day that I can get up out of the bed.

MATT BACOATE, JR.: Mental therapy, physical therapy, and sport.

CY YOUNG, JR.: But however, it's the challenge is what I love about playing golf.

It's the challenge.

It's the pure challenge.

PETE MCDANIEL: Because nothing beats you up like golf, just absolutely hammers you on days.

But then the next day, it may kiss you on the cheek and leave you just totally in love all over again.

SPEAKER 2: I think it helps my mental outlook, just generally, you know.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: I just put Christ first, family second, and then golf.

CORTEZ BAXTER: When everything cut and dried, said and done, the swing is the thing.

Upper body, lower body-- it's got to move together.

It's just like music-- harmony.

Everybody knows the Muni.

Just about everybody in western North Carolina that learned to play golf, this is where they learned to play it, including me.

[jazzy music] DARIUS RUCKER: Like it is today, on most mornings at Muni-- in the 1920s, golf had captured the interest and imaginations of many.

And in this booming city of Asheville, North Carolina, public parks were being built for the residents and tourists, including a public golf course.

It was to be one of the finest courses in the country, according to the designer.

But it would not be so difficult for the average golfer to despair.

And it was said that at $0.50 a round, the course would soon pay for itself.

KEITH JARRETT: You know, it was the first municipal golf course in North or South Carolina with the intent of getting the golf to the common man.

DARIUS RUCKER: The course designer would become a legend.

And his name was Donald Ross.

He was a Scotsman.

He had come to America with $2 in his pocket.

Quickly establishing himself, first as a player, and then as the foremost builder of golf courses.

The farmland along the Swannanoa River soon became the Asheville Municipal Golf Course, which opened in 1927.

While Ross built both private and public courses, he was on record saying, there's no good reason why the label "a rich man's game" should be hung on golf.

CY YOUNG, JR.: To me, Muni is very historical because that was where the Blacks first started playing.

[music playing] BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Two fellow friends of mine was talking about caddying the Biltmore Forest.

And the money that they made, $3 and $4-- back in '45, that with a lot of money.

And I went to the golf course with them.

And the first day there, I made $3, man, and I thought I was rich.

So that's what started me to caddying, you know.

DARIUS RUCKER: The guys who were caddying here at the Muni and the other clubs in the 1940s and '50s were carrying on a tradition that went back a few generations.

Golf had come to Asheville and many places in the South during the later part of the 19th century.

And photographs through the decades show the close relationship African-Americans had working at the clubs, often carrying the clubs.

It was money, yes.

But it was, as you might say, a mixed bag.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Well, you had some good guys and you had some that had nothing to do with you, or whatever.

DWIGHT BRYSON: Oh man, you got jerks everywhere you go.

I don't care what you do.

But try not to work for 'em or caddie for 'em.

Sometimes you had to, and sometimes you didn't.

DARIUS RUCKER: But it introduced them to the game that would change their lives, learning it and playing it any way they could.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Well, we learned our swings from the guy that we caddied from.

PETE MCDANIEL: The takeaway, how they set up to the ball, and all of that-- we got that from them.

DWIGHT BRYSON: And if you found a 5 iron, a 4 iron, that was the club you mastered, and you played with it.

So after that, I was a pro then, I thought.

CORTEZ BAXTER: Now, y'all will make the second course.

And it's-- they're on the tee right down there.

Now, just go right down the hill.

You'll see 'em.

The starter-- I get everybody lined up.

Like today, it wasn't no sweat.

But some days, it's hectic.

You know what I mean?

You got folks impatient.

If you can't drive, turn your license in.

It's just something that I like to do.

In fact, I don't know what I would do if I didn't have this to fall back on.

And I enjoy it thoroughly.

I mean, it's not work to me.

PETE MCDANIEL: He's someone who is totally in love with the game of golf.

You want to see an old-timer who eats it, lives it, breathes it?

That's Bax.

[music playing] CORTEZ BAXTER: I never thought it'd go this far.

I never thought I'd get this deep in it.

But I get deeper and deeper.

MATT BACOATE, JR.: I've been charged with Cortez stating that I'm the one that got him hooked.

CORTEZ BAXTER: A friend of mine, he brought a 7 iron to work one night.

He wasn't a golfer.

Wasn't none beside a crew out there of five-- cleanup crew.

We started pitching around with that club.

But they had horseshoe boxes.

I don't know what the distance horseshoe-- but anyway, we'd chip with that 7 iron.

And one day, one of the guys said, let's go to the golf course.

I said, well I don't have a club.

I don't have-- didn't none of us.

The only thing we had between us was that 7 iron.

And we came out here and we just knocked it around.

I shot a-- I was living at 111 Bland Street.

I shot 111 that day.

That's the reason I remember it so vividly.

That was pure, there.

If I wasn't learning, I'd turn it loose.

But I learn something every time I pick up a club.

I tell folks that, and they look at me like, you're crazy.

But I do.

It's so much to learn.

It's a big, big game.

PETE MCDANIEL: Billy was a stud-- like, larger than life.

They called him Black Jack-- you know, the Black Jack Nicklaus.

Big man, could hit the ball a mile, a great short game.

He was friendly when he knew you.

But if he didn't know you, he could be kind of stern.

And that's how we kind of looked up to Billy, although he wasn't that much older than we were.

He was like an elder statesman because he had so much experience.

He was a great player.

And he-- you know, he kind of took over Black golf in this area, to be honest with you.

CHARLIE COXIE: I played a lot with Billy, and Billy could hit it.

Billy could hold his own with it.

He and I would play, and we'd have a lot of fun together.

Billy's like me.

He's getting a little old now, and he can't get around like he used to, but he's still Billy Gardenhight.

CG ROBINSON: I'm glad see him out here.

This has been his life.

This has been his life-- golf.

I'm glad to see him up, come back to playing after he had that leg taken off.

You know, you think about that.

If he didn't golf all his life, he couldn't do that.

You don't know.

You know that?

You don't know.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Well, my mom, she always told me to don't be afraid to do what you got to do.

So we'd be walking through town a lot of times, and people used to step off the sidewalk to let white folks by.

And she'd tell me to stay on there, you know.

So I just grew up that way.

Most stores had two fountains.

They had one white and one colored.

Sears & Roebuck and all those places, that we couldn't-- wasn't supposed to drink out of the white fountain.

And when we got to high school, a lot of us used to say, we don't want no colored water today.

We want white water.

We'd go over there and get run out the store or whatever.

That's more like it.

DWIGHT BRYSON: Most Blacks couldn't play out here until Mondays.

We couldn't play.

But I could sneak on the back nine.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: No, when I first saw it, you know, they had what they called Caddies' Day, which was Monday.

So I started hanging around the clubhouse, picking up balls and washing down the porch.

At the age of 13 I started playing pretty good.

And they would take me around and they would gamble.

And if we won money, I'd get a little bit.

So that's the way I really got started.

[music playing] SPEAKER 3: Aww, man.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: People would drive by the golf course and they'd holler at ya and throw stuff out the car at m or whatnot.

Back when they did change, in 1954, when they made the ruling that they had to integrate public parks, a fella named Boris Layton and myself went to the golf course on Sunday.

I had a lot of miracle.

I wasn't scared.

And the next day in the paper, it had Negroes show at golf course.

And people in Beverly Hills talking about selling their houses and whatnot.

And it went on like that for a few days.

Then the golf clubhouse got burnt down, so they figured that someone set the clubhouse on fire because of this.

But at that time, a lot of Black folks were just afraid to do things because things would happen to them sometime.

DARIUS RUCKER: Even before the fire, it was clear that many in Asheville opposed desegregation at Muni.

The city entertained offers to sell the course to a private group in order to skirt the desegregation issue.

But Billy and others protested at the city council meeting, and the sale was stopped.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: The lawyer asked me to make a little speech.

And I made a speech that I would like to be a pro one day and please don't sell the golf course, and whatnot.

Councilmen laughed at us, said y'all boys go on back home.

We ain't going to sell that golf course, you know.

And here we are with a lawyer and another elderly man.

They called them boys.

You know, so things like that, you know, stick with you all your life, you know.

DARIUS RUCKER: The city rebuilt the clubhouse without the second floor.

But over the next few years, integrated play increased, and Asheville Muni became the first municipally owned public course in the South to embrace full desegregation.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: But after we got started, man, they start flirting.

I said, oh.

PETE MCDANIEL: But this was freedom.

This gave us a place to play.

That's the greatest part about golf is that it's an individual effort.

It's you, the golf ball, and the golf course.

No one can influence that-- no one.

You're totally in control.

And for people-- or a people-- who had never been in control of anything, I think that was a real appeal of the game of golf.

DARIUS RUCKER: After Billy and the other African-Americans flooded out to Muni and played any day they wanted, in 1959 a group of players organized the Skyview Golf Association and Tournament.

Its hope was to promote golf in the Black community and help players to become professional.

The first Skyview Golf Tournament was held in 1960.

And it soon became one of "the" tournaments on the African-American golf circuit.

[music playing] CORTEZ BAXTER: Skyview was the biggest thing in Western North Carolina.

DWIGHT BRYSON: Big, big major event.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Well, the best year, we had 254 golfers.

DWIGHT BRYSON: People from north, south, east, west-- they're coming in Cadillacs.

They're coming in Buicks, Fords, even taxicabs.

CORTEZ BAXTER: Well, it's got a long, colorful history.

CHARLIE COXIE: Yeah, I've seen this place just covered up with people.

You couldn't be-- you couldn't get a parking place anywhere around here.

PAUL EVERETT: I remember back in the day when you would have crowds of people actually lined up on the front side and on the back side.

MATT BACOATE, JR.: Many of the golfers who became PGA players, they play here every year.

DWIGHT BRYSON: And these guys, they all play in what's called the Chitlin' Circuit.

And they play in their tournaments all around, you know.

CORTEZ BAXTER: We had some tremendous golfers come through here.

PETE MCDANIEL: You name it, they played here.

Lee Elder, Charlie Owens, Chuck Thorpe, Jim Thorpe, Jim Dent, James Black, Nate Starks, Bobby Stroble, all the greats played here, in this tournament.

If you were a Black golfer and you were worth your salt, you played in the Skyview.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Oh, man, I know it was-- it was beautiful to see-- at that time, I would say in 1963, '64, that many Black folks mixed with a few white folks.

PETE MCDANIEL: And these guys were good.

They'd come on this golf course and shoot 63, 64, or 65.

CY YOUNG, JR.: The first time I remember is this guy was on the pro team-- Black guy-- and his name was Chuck Thorpe.

And Chuck was getting ready to hit the ball on the first tee, and he was using the 3 wood off the ground, and knocked it on the green.

And I thought, holy cow, that man can play some golf.

And guess what?

He was tough.

I'll never forget him.

Heck of a golfer.

PETE MCDANIEL: There weren't many tournaments that Blacks could play in.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Well, it had never happened before like this.

They had had tournaments, but usually it was a tournament that was sponsored by white folks in Miami or California or somewhere like that.

But Asheville, North Carolina?

DWIGHT BRYSON: It was good for the community.

Most of the adult Blacks knew the Skyview was coming to town.

It was like the parade, Christmas parade.

"Skyview's in town.

Skyview--" BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Skyview really was jumping at one time.

I mean, we had a party on Thursday night.

And we'd have a thousand people at the dance.

DWIGHT BRYSON: Band, banquet-- they'd call your name on the speaker.

"And winner of first place--" MATT BACOATE, JR.: Beautiful feeling that it created within me, and, I'm sure, many other Negroes.

It had an indelible mark.

[music playing] PAUL EVERETT: I really wish that African-Americans knew about the history of what took place as their participation increased in golf.

And you have quite a few golfers now who have no idea of back in the day when we had to go live in the private homes, because we weren't allowed to live in the motels and hotels in Asheville because of the Jim Crow laws.

And, you know, that evolved.

And how I can tell you stories that you probably wouldn't believe, but a lot of the guys-- I know of one guy, Bobby Stroble, he would travel with a frying pan in his golf bag because we weren't allowed to eat in certain restaurants and whatnot.

And you just did the best you could with what you had.

But the stories are plentiful.

JESSE ALLEN: Well, this was one of the only places we could play, you know, back in the day.

They got a lot of history.

Most all of the Black pros that really-- that played the Tour used to play the Skyview.

Back then it was more African-Americans on the PGA Tour, back in the '60s and '70s, than it is now.

Because they had these type tournaments where you could play every week.

So this was like a springboard to trying to get to the PGA Tour.

But now you don't have-- either you play the PGA Tour or play the Web.com or you go find a job.

PETE MCDANIEL: It was a place for them to play competitively and earn a little bit of money and plus get their hustle on.

Which it was-- they a lot of times made more money hustling than they did from the golf tournament purse itself.

KEITH JARRETT: Chuck Thorpe, quite a character.

You have part of the Thorpe golfing family.

He won the Skyview five or six times.

They came to town and it was just-- it was rollicking.

And all these guys were like that.

They were characters.

And you don't see that much anymore.

And it's-- I miss that.

And I miss that part of the Skyview.

But it was fun back in the day.

DARIUS RUCKER: 60 years later, the Skyview tradition continues every July, with Billy still running the tournament from the registration table.

PETE MCDANIEL: I left here in 1993.

So I've been gone 25 years.

DARIUS RUCKER: And a kid that grew up in Muni comes back to stay connected to his roots in golf.

PETE MCDANIEL: It's 10-over, right now.

But that's all right.

CORTEZ BAXTER: Is that right?

PETE MCDANIEL: That's all right.

They're family, plain and simple.

Most of these older guys helped raise me.

LONNIE GILLIAM: I remember when you were a little baby.

PETE MCDANIEL: It just warms my heart just to see them, and see them still above the divot, as I say, and still loving this game.

Richard Pea, what's happenin', baby?

RICHARD PEA: How you doin' brother?

How's everything?

PETE MCDANIEL: How you doin', my man?

RICHARD PEA: Good seein' you, man.

LONNE GILLIAM: I guess I've been coming out here for 40some years.

And it's almost like a homecoming, because as soon as you see each other, you want to hug each other.

You want to greet each other with some real meaning and strength of all of the years that goes by.

And that's really what's important.

[music playing] DARIUS RUCKER: The tournament continues to bring people together.

FRED TURMAN: I'm ready to get out here and see what I can do this morning.

DARIUS RUCKER: With folks like brothers Fred and Leroy Turman making the trip from Chicago every year to compete on the course they grew up on.

FRED TURMAN: I'm one of these guys, I don't care how well I know you, when I tee it up my whole attitude changes, because I'm a winner.

And I believe that I can beat the average guy out there.

PETE MCDANIEL: They're all nervous.

They're out here today playing in a golf tournament, and it changes everything.

Your nerves are on edge.

LEE SHEPHERD: Hey guys, glad to see everybody again this year, as usual, for the Skyview.

The field is a little light this year.

But next year it'll be full.

I guarantee you that.

I promise you that.

PETE MCDANIEL: I would like to pay homage to the people whose shoulders we stand on today, members of the Skyview Golf Association.

CY YOUNG, JR.: I can't say enough about Billy.

He's a pioneer.

And he's the one that engineered the Skyview.

And he's really pushed it hard.

And it makes him feel good whenever he is able to see so many people coming out for it.

LEE SHEPHERD: This is Billy Gardenhight, the director of the Skyview Golf Association.

He's also my father.

But if you would, give him round of applause.

[cheering and applause] [music playing] PETE MCDANIEL: You see all of these old people out here.

It's a bygone era.

We're still holding on.

We're still playing.

We're still enjoying the game.

But we just didn't transfer our love of the game to our kids.

KEITH JARRETT: Especially in the Skyview, I don't see young African-American golfers.

I haven't for years.

That's unfortunate and I hope that trend will change.

PETE MCDANIEL: A golf tournament that has meant this much, which has that much history, can't just go away.

And the way for its legacy to live on is through youth.

[music playing] DARIUS RUCKER: And Billy?

He soldiers on, playing every day he can, enjoying every round he can.

BILLY GARDENHIGHT: Well, I love it.

I'm just glad I'm able to come out and play.

Some people, when they have amputations and things like that, they just give up.

I'm not giving up.

I says I'm gonna keep going till I-- the good master come after me.

[music playing] FRED TURMAN: I enjoy seeing this, because I see the people are coming together.

And I really feel that this is the way it should be all of the time.

PETE MCDANIEL: How are we going to get to know each other unless we get to know each other?

You know what I mean?

And the golf course is a perfect place to meet people, people who may not have anything in common except trying to play this game.

CORTEZ BAXTER: I just enjoy life.

I enjoy it.

[music playing] My wife told me one day, said, honey, you gonna die on the golf course.

I said, I'd die happy.

[funky music playing] ♪ ♪

Creating a Black Golf Tournamnet

Video has Closed Captions

Flashback to the 1970s an this prominent Black golf tournament. (2m 11s)

Video has Closed Captions

Black Asheville natives tell it how it is growing up in a segregated society. (1m 2s)

Video has Closed Captions

A jovial love letter to the game of golf, told by the Black golfers in Asheville, NC. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for Reel South is made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Center for Asian American Media and by SouthArts.